<p style="text-align: justify;">It&#8217;s interesting which parts of science fiction come true, and which do not. As early as the 1960s, science fiction novels, TV shows, and movies began predicting that some day we would be able to video chat in real time both across the planet <i>and</i> from outer space; none of them, on the other hand, correctly speculated that the same technology that was used to develop what we now know as Skype and FaceTime would only come after the invention of the internet. In fact, no sci-fi story ever predicted the internet would happen.</p>

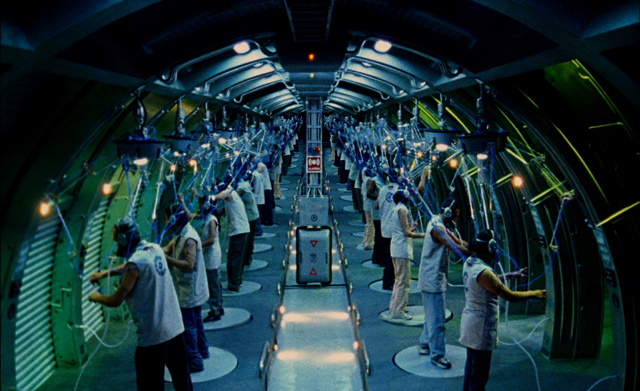

<p style="text-align: justify;">Piers Anthony&#8217;s <i>Killobyte</i>, first published in 1993, is another example of where sci-fi predictions succeed and where they fail. <i>Killobyte</i>, like many other novels&#8211;including Ernest Cline&#8217;s <i>Ready Player One</i> and Neal Stephenson&#8217;s <i>Snow Crash&#8211;</i>takes place in an extensive, full-sim virtual reality universe, the type that involves users to wear over-the-face helmets and body suits packed with sensors to ensure that their real-world movements affect their virtual avatar.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><img class="aligncenter size-Correct wp-image-9383" alt="What Sci-Fi Gets Right, and What It Gets Wrong" src="https://medusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/What-Sci-Fi-Gets-Right-and-What-It-Gets-Wrong-600x366.jpg" width="600" height="366" /></p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">Although these types of virtual reality experiences, including helmets and sensors, do exist &#8212; a few get demonstrated every year at gaming conventions like PAX &#8212; they&#8217;ve never really caught on in the way that sci-fi authors have predicted they would. (Why not? A few factors. The first is cost: those VR helmets and body sensors don&#8217;t come cheap. The second is mobility; these types of games nearly always require external spotters to ensure the helmeted individual doesn&#8217;t get too excited about the virtual gameplay and, blinded by the VR helmet, run smack into a wall.)</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">But what&#8217;s really interesting is what <i>Killobyte</i> didn&#8217;t predict. The main character, Baal Curran, has type 1 diabetes; one of the main plot thrusts of the novel involves her attempt to manage her disease while moving between the real and virtual worlds. We quickly learn that, for Baal, monitoring her diabetes is a full-time job; her boyfriend recently left her because he could not handle the continual caretaking aspects involved in the disease, and the reason Baal spends so much time in the virtual universe is because she feels unable to do little else.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">Piers Anthony, who developed diabetes himself later in life, was able to imagine a futuristic world in which virtual reality was commonplace, but was not able to imagine a world where diabetes management was as simple as real-time glucose monitoring. Though <i>Killobyte</i> takes place in &#8220;the near future,&#8221; Anthony didn&#8217;t put together that a world in which networked computing and full-body VR suits exist would also probably provide options for diabetes management that didn&#8217;t include the injections and test strips available in 1993.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>In Short:</strong> Anthony got a lot of it right, but he didn&#8217;t predict the DexCom Seven, in which users wear a small wire underneath their skin which sends glucose information to a wireless device, enabling real-time diabetes monitoring &#8212; for more information, see DexCom&#8217;s website.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">Nor did he predict that a fully-immersive VR world in which characters run, jump, swing swords, and hug would require a full-time, external spotter <i>not</i> involved in the VR world, to make sure Baal didn&#8217;t hurt herself as she was hacking and slashing.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">He didn&#8217;t predict that the internet and tabbed browsing would make the primary conflict of his novel &#8212; can Baal escape the VR world in time to check her insulin &#8212; obsolete; now Baal would simply monitor her levels in-game, or in another tab along with the rest of her vital statistics.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">It&#8217;s fascinating to look back and see what sci-fi gets right, and what it gets wrong. In the end, the technological predictions are often correct, but the social implications are not &#8212; the idea that networked computing would be used to monitor health as well as create elaborate games, for example.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">What do you think our current sci-fi stories are missing? Let us know in the comments.</p>

What Sci-Fi Gets Right, and What It Gets Wrong